Bulletin photos by Jonathan Polen

By Julia Hutchins

Bulletin Correspondent

Sexual assault has become an increasingly prevalent topic in the news, especially with the current #metoo movement. That doesn’t make it any easier to write about or to talk to people about, as panelists discussed at a session on “Reporting on Sexual Assault: The journalistic, emotional and legal challenges” at the New England Newspaper and Press Association’s recent winter convention.

“It’s a topic I’ve been grappling with,” said Rob Bertsche, who specializes in media law and First Amendment law as a partner at Prince Lobel Tye LLP, based in Boston. He led the discussion panel Saturday morning, Feb. 24, before an audience of about 35 people. “It’s a hard issue, and there are few good answers.”

The other panelists were Priyanka Dayal McCluskey, a health business and policy reporter for The Boston Globe, and Michael Blanding, an award-winning investigative journalist whose work has appeared in multiple publications, including The New York Times and The Boston Globe.

Although reporting on sexual assault is outside her usual beat, McCluskey recently wrote a story on a suspended head of health care at 1199SEIU United Healthcare Workers East, a Boston-based affiliate of the Service Employees International Union, who reportedly engaged in lewd behavior.

“I was impressed with the number of people who volunteered (themselves to be interviewed) to me,” McCluskey said. “There were more than we could use in the end.”

Not everyone is comfortable with speaking up about sexual assault, Blanding said.

Not everyone is comfortable with speaking up about sexual assault, Blanding said.

“If they’re not ready to tell their story in a way that they may be challenged on it, they may not be ready to tell it at all,” he said.

Even checking information and getting both sides of a story can shut down sources, McCluskey said. “There is a risk of, when it is known that you’re working on something, that (someone) will try to shut up your sources.”

One of the major pitfalls a reporter can face is taking the side of the person making the accusation, in an attempt to make that person feel comfortable. That can mean anything from not contacting the alleged abuser to not checking facts.

Verifying facts is incredibly important, Blanding said.

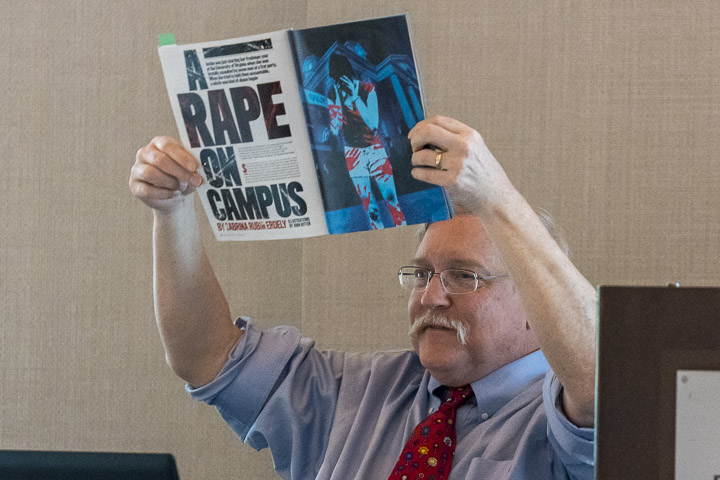

He said that “checking more than you think you need to” will both strengthen a story and validate it, as Rolling Stone magazine discovered after its notorious, and false, 2014 story about an alleged gang rape at a University of Virginia fraternity house party. The story included the account of a young woman who claimed to have been gang raped at the party, and the university’s purported subsequent lack of response. The story was later found to be fabricated; the fraternity in question did not even have a party that night. Although the reporter, Sabrina Rubin Erdely, was experienced, she had fallen in a trap of trusting the source to be telling the truth and promised not to follow up on conversations, which would have disproved the story immediately. The story prompted at least three lawsuits. One resulted in a $3-million judgment against Rolling Stone and Erdely. Another resulted in a $1.65-million settlement against Rolling Stone. The story also damaged the magazine’s reputation.

The thought that “most women are telling the truth and wouldn’t put themselves through this, doesn’t work as proof of truth,” Bertsche said.

Given the sensitive and taboo nature of sexual assault, lawsuits are not unexpected when accusations fly. That has become especially relevant recently, as allegations of sexual misconduct and assault have resulted in people being removed from powerful positions in government, business and the entertainment industry.

Reporters can often find themselves in difficult situations, because accurately reporting on something outside official court proceedings can make them liable, Bertsche said. With no official transcript or records, the offended party can use libel lawsuits against the journalist or his or her news outlet or both.

“From a lawyer’s perspective, if you’re never threatened by a lawsuit, you’re not doing your job. But if you’re surprised by a lawsuit, then you’re also not doing your job,” Bertsche said.